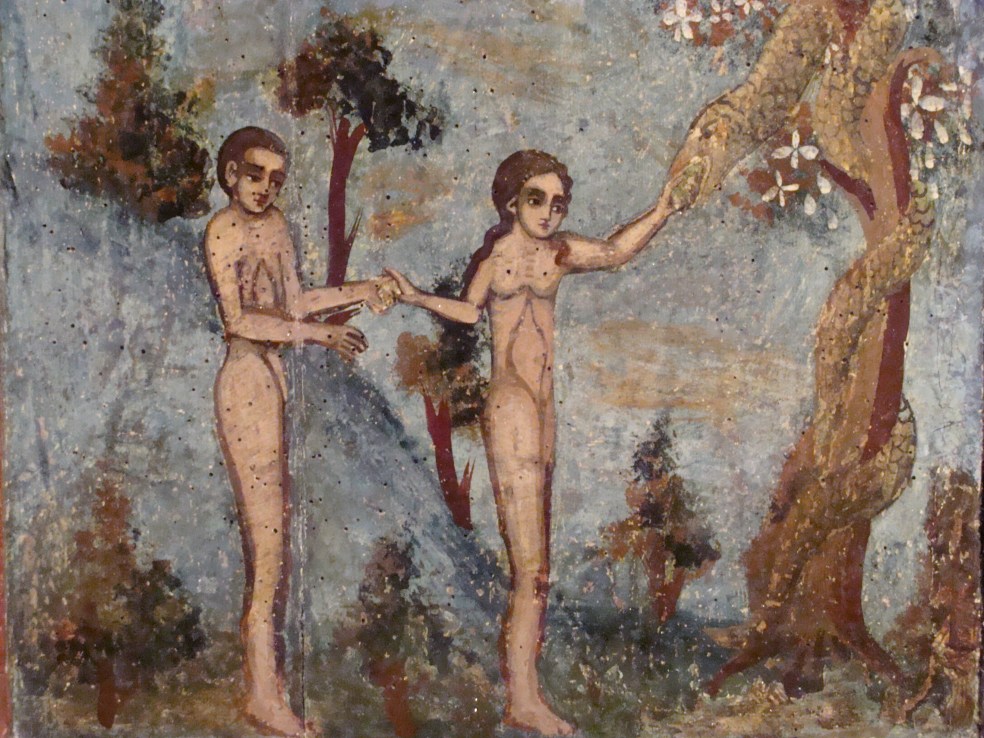

The story of the Fall of humankind is related in chapter 3 of the Book of Genesis. It is generally understood to mean that the woman, Eve, was tempted by the serpent and persuaded Adam to eat of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, which the Lord God had told the man not to eat from or else he would die. The serpent – a representation of evil, or the devil himself – tells Eve that they will not die, but their eyes will be opened and they will be like God, knowing good and evil. The man and the woman eat and then become aware of their nakedness, which causes them to hide when God comes visiting ‘at the time of the evening breeze’. The Lord God asks Adam how it is he knows that he is naked, and he replies that the woman gave him fruit from the tree to eat; she in turn blames the serpent. God pronounces their punishment, and the man and the woman are expelled from the Garden of Eden.

I should perhaps point out one of the most remarkable word connections you will ever find, and that is when we rearrange the letters of GARDEN OF EDEN. I used to do this, sitting down in the early morning (between 6 and 8) while the house martins screeched around on a level with my eighth-floor apartment in Sofia, Bulgaria – rearrange the letters and see what I could find.

GARDEN OF EDEN gives DANGER OF NEED. This is surely a coincidence, language telling us something.

Adam and Eve were in danger of need. But what exactly is wrong with having a knowledge of good and evil, and why should that cause them to die?

I would like to suggest an alternative interpretation, one I thought was unique to me until I discovered that it had been offered and accepted before. This interpretation – which is only that, an interpretation – gives rise to several conclusions, which I would like to list at the end of this article.

I imagine Adam and Eve playing in the Garden of Eden, in innocence, as children do, without a care in the world and with not much to do except to admire God’s handiwork in themselves and the animals and plants that surrounded and delighted them. They must soon have become friends. Life must have seemed like an ‘Eden’ to them – no great responsibilities, no great amount of work, no aches and pains to bother them. Just an eternity of today.

Except, as children do, they began to grow, to become sexually mature, and their curiosity must have been piqued. Eve began to have these bumps on her chest; Adam began to grow hair around his genitals and his long thing got longer. And they must have begun to experience the first sexual stirrings, perhaps in the night, when they were asleep, lying among last year’s fallen leaves. Perhaps they began to experience pleasure and to wonder what pleasure lay in the other.

There is an obvious correlation between the serpent and the man’s penis. The snake has traditionally been associated with the penis and sexuality. So perhaps it was the man who, feeling aroused, suggested they acquire carnal knowledge, knowledge of one another. Certainly carnal knowledge can be for good and evil – good in a loving, committed relationship and in the procreation of children; evil when it treats the other as an object and seeks only its own satisfaction. Undoubtedly, in the history of humankind, sex has been a force for good and evil – on the one hand, a demonstration of love, two people coming together in wonder and amazement; on the other, an abuse of the other person when it is not consensual or merely pleasure-seeking, seeking a meaning where none is to be found.

So we have identified the serpent with the man’s penis, but what of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, the apple? The apple can be related to the woman’s breast, that object that mystified the man and that he is now suggesting they eat of. After all, a fruit has flesh. It also has ‘the seed in it’, as we read in chapter 1 of the Book of Genesis, in the first creation account.

God had said that if they ate of the forbidden fruit – had sexual intercourse – they would surely die, and this is true, but bear in mind that the verb ‘die’ has two meanings: to expire at the end of our earthly lives, but also to expire in orgasm. This latter meaning is well documented.

What is the connection between these two meanings, and again why should the knowledge of good and evil be such a bad thing?

I think the answer is to be found in an article by a Greek bishop and theologian, Metropolitan John Zizioulas. In ‘The Consequences of Man’s Fall’, he writes, ‘In beings with organs – especially mammals – the ageing cycle begins from the moment that the organism reaches the point of reproductive maturity.’ So when we reach sexual maturity, we begin to die (in both senses of the word).

And this ties in with a teenager’s behaviour, because a child who reaches sexual maturity changes somewhat. They become more bashful, more private, they are no longer prepared to appear naked in front of their parents. Isn’t this exactly the behaviour of Adam and Eve when God comes looking for them ‘at the time of the evening breeze’? They hide themselves. They have become aware of their nakedness. And what is it they use to hide their nakedness that now causes them such shame? Fig leaves! Figs are another symbol of sexuality and the male organ.

So they have acquired carnal knowledge, they have slept together, and now they do not want God to see them because they are ashamed of their nakedness and they know that he will see it in their eyes. Their eyes have been opened.

But if sexual maturity coincides with the beginning of the ageing process, there is no other way to have children. So God – who so often is seen as inflicting punishment, as being vindictive, something that is as far away from his nature as it is possible to be – performs an act of charity, of love: he banishes them from the Garden of Eden in case they eat of the tree of life. He wants them to have children (I’m quite sure he knew perfectly well what was going to happen, just as any parent does), but he doesn’t want the ageing process that comes with sexual maturity to last for ever, that would be terrible, so he sends them out of the Garden of Eden to till the land they came from.

He does this in order that we might have children. In order to have children, we must die. This is the meaning of death – it is so that we can have the unparalleled blessing of procreating, of giving our life to another, who is then ‘the apple of our eye’.

This is a great thing – ‘Greater love hath no man than this that a man lay down his life for his friends’ (Jn 15:13) – but it also serves another purpose: it builds up the body of the Church. It prevents God from having to create all the creatures, all the men and women, himself. He involves us in the process (albeit our involvement is slightly different, because life passes through us, it does not begin with us – we are translators, not authors).

In this sense, the earth is a spiritual womb, it is a womb in which a spiritual body – the body of the Church – is being formed, just as we are formed in our mother’s womb. We have not realized this. Just as there is spiritual blindness as well as physical blindness, so there is spiritual birth as well as physical birth. We are still in the womb, but now it is not the body of an individual that is being formed, it is the collective body of the Church, a body made up of many members (in 1 Corinthians 12 and Romans 12, Paul compares us to the different members of the body, each performing his or her own unique function, with Christ as the head).

And this is where we get into the realm of Christian paradox: life passes through us when we receive life from our parents and pass it on to our children; but we also pass through life, in the sense that we are not here for ever and we move on. We form part of the body of Christ, the body of his Church, but in the sacrament of communion it is his body and blood that form part of us. We lose our life and find it. I begin to think the Christian message is true precisely because it is paradoxical.

Is there an indication of the world as a spiritual womb? I think there is, because if we read the first creation account in chapter 1 of Genesis, we find that God created the day on day one (already we have the progression AIO in the word DAY, remember the correlation between O and D and between i and y) and then, on day two, he created the dome of the sky by separating the waters from the waters. Doesn’t that sound like a baby in its mother’s womb, surrounded by water? Perhaps this is why SKY can be connected to KISS and SICK, because for procreation to occur there must be a kiss, but sexual maturity is also the beginning of the ageing process, of what makes us sick.

Is there anything in language to connect the serpent and the man’s penis, to connect the apple and the woman’s breast?

Well, if you allow fluidity to the vowels and change one front vowel for another, you will find that PENIS is in SERPENT, with the addition of r and t. And applying the phonetic pairs b-p and l-r, you will find that APPLE is in the first four letters of BREAST, with the addition of s and t.

This interpretation – and it is only an interpretation – has three consequences:

- The Fall was a good thing. Otherwise, we couldn’t have children and the body of the Church could not be formed.

- Perhaps the woman is not entirely to blame; in fact it would seem that Adam was the prime mover in response to his sexual desire. We could at least speak about shared responsibility.

- While in the Church great emphasis is placed on monasticism, on abstinence and asceticism, it would appear that the purpose of life on earth is to have children, and this would give the option of marriage far greater importance than it is sometimes credited with.

So Genesis, that most remarkable book, is not just the story of the creation of the world and the Fall of humankind, but also the story of each one of us, of human life. We are born, just as the world (the body of Christ) is. We reach sexual maturity in order that we might give that life to others. We then have to die (we have now fast-forwarded to the Crucifixion) because it is the only way to give life – to die, to expire. But there is a greater mystery here. This is not the last word.

The word ‘die’, if we apply the physical pair b-d (a pair of letters that look alike; in this case one is the mirror image of the other), clearly contains ‘I’ and ‘be’. It is a very life-affirming word. The word ‘live’, if we remember the closeness between b and v, contains two ‘I’s and ‘be’ – this may refer to our physical and spiritual selves, to our human and divine natures (the latter acquired by grace in a process known in Orthodoxy as theosis), or to our fallen and resurrected selves. Anyway, it is manifestly not the end.

If we could only see this world for what it is, a place of spiritual growth (not a place to make money!!) – a spiritual womb – we might realize our connectedness. Having been born from our mothers, we are now – all of us, outside the constraints of time – in the process of forming another, spiritual body, one that has Christ as its head and one that will last for all eternity. The world is a spiritual womb. We must die in order to have children, participating in this way in the formation of the Church. And having died, we have no choice but to be born again, but this time without the straitjacket of corruption, without the ageing process. We will be ‘like angels in heaven’ (Mt 22:30). With one great difference: we will not be alone.

Jonathan Dunne, http://www.stonesofithaca.com

Pingback: Word in Language (10): Father (0) – Stones Of Ithaca

Pingback: Word in Language (11): Father (1) – Stones Of Ithaca

Pingback: Word in Language (13): Hate – Stones Of Ithaca

Pingback: Word in Language (14): Auxiliary Verbs – Stones Of Ithaca

Pingback: Word in Language (18): Mary, Mother of God – Stones Of Ithaca

Pingback: Word in Language (20): Believe – Stones Of Ithaca

Pingback: Word in Language (22): English Course (1) – Stones Of Ithaca

Pingback: The Fall – Stones Of Ithaca