Turner’s painting Seascape with a Yacht (?), c. 1825-30, is somewhat cursorily dismissed on the Tate Gallery website. It doesn’t get a display caption, like most of the paintings. There is a catalogue entry, but it is short and rather scathing – “thinly and freely painted […] lack of drama and small size” – and ends: “There are some losses down the left-hand edge and particularly at the top corner. The picture has not yet been restored.” No wonder it wasn’t put on display.

There even seems to be uncertainty about the title (that question mark in brackets) and about the date (circa a period of five years). Everything points to a painting unworthy of our attention. And yet it is the gift of the poet to see something extraordinary in the ordinary, and in her book Turner and the Uncreated Light the Bulgarian poet Tsvetanka Elenkova does just this. Let us look at the painting:

Not much, right? A splodge which is falling to pieces. There appears to be a yacht (is it a yacht?) on the right, and some waves. But the poet has noticed the predominantly ochre colour of the painting. The sea looks less like a sea than a desert. The yacht she understands to represent the people of Israel crossing the desert. And that tall white wave at the bow of the yacht she takes to be the prophet Moses.

Then she draws our attention to the large blue area in the left half of the picture, standing, as it were, on the waves. She understands this to be Archangel Gabriel. We can see the fold of his tunic where it crosses on his chest, in a lighter colour. Out of the tunic appear his neck and head. He is looking towards the yacht, watching over the people of Israel as they make their way to the promised land. Behind him (again in a lighter colour) we can see the outline of his wings.

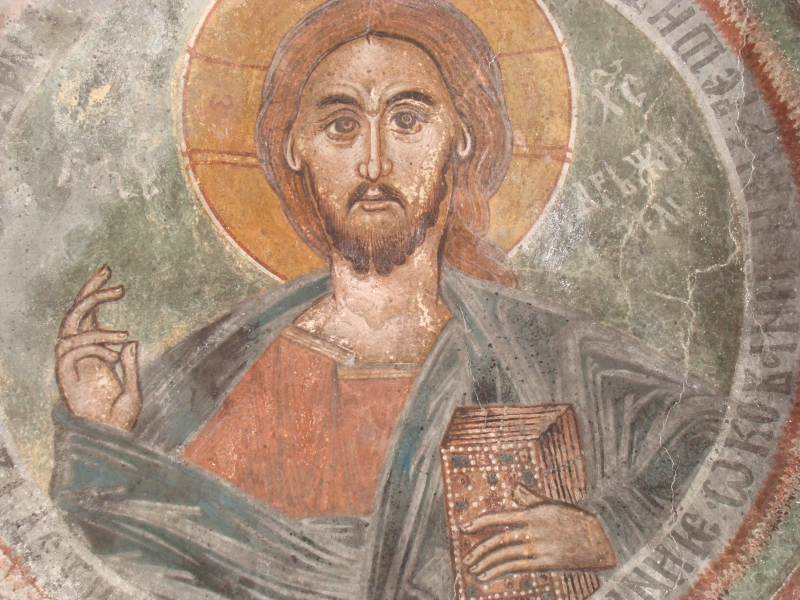

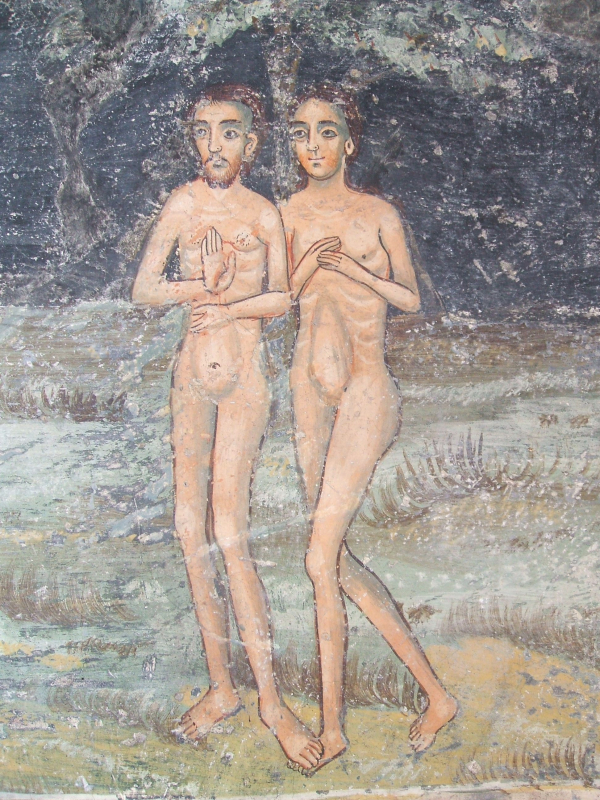

It may help at this point to reproduce a fresco of Archangel Gabriel found in the medieval Church of Sts Peter and Paul in the old Bulgarian capital Veliko Tarnovo (in central Bulgaria) because there is an obvious similarity between the two images:

Again, the tunic is folded over on his chest. The angel’s skin is darker than the cloth of the garment. And we can see the outline of his wings. He is writing on a scroll (“Wash yourselves and be clean learn to do good”) – perhaps that is the meaning of the dark blue patch to the right of the angel in Turner’s painting.

And in the painting she also sees a horse’s head in the ochre sky above the yacht and slightly to the right. It is possible to make out the horse’s eyes and nostrils. Admittedly we can always disbelieve. Then the magic of the painting begins to recede, and we are left with a tattered painting. But the poet’s vision is so much richer. Here we have a depiction of the Exodus – this is why the painting has not been restored, we haven’t got there yet. We are on the way, a prophet leading us, a guardian angel over our shoulder. As with the other paintings, not for a moment do I think Turner consciously painted these things. It’s just he received the same inspiration as the painter of the fresco in a church in central Bulgaria several hundred years earlier. It is the same Spirit working through him.

Jonathan Dunne, http://www.stonesofithaca.com