Starting Coordinates: 42.46882, 23.27801

Distance: 13.2 km

Elevation Gain: 405 m

Time: 4½ hours

Difficulty: moderate-hard

Transport: by car, or by bus no. 69 just past Zheleznitsa (this still leaves a significant distance)

Yarlovo is the other most distant village you can reach on the south side of Vitosha, together with Chuypetlovo, the difference being that you come at them from different directions. To reach Chuypetlovo, you go west around the mountain. To reach Yarlovo, you go east, via Bistritsa and Zheleznitsa. The two villages are actually in adjoining valleys – Chuypetlovo in the Struma valley, Yarlovo in the Palakaria valley – so visiting both villages is like putting your arms around the mountain from both sides, a fitting way to bring this book to a conclusion.

Yarlovo is again about fifty kilometres from central Sofia, an hour’s drive. You pass through Bistritsa, Zheleznitsa, the villa zone known as Yarema, until you reach Kovachevtsi. From Bistritsa to Kovachevtsi is 22 kilometres. Shortly after entering Kovachevtsi, there is a turning on the right for Yarlovo, 5 km. The furthest you can get with public transport is bus no. 69, which takes you just past Zheleznitsa, but that still leaves a significant distance to Yarlovo (about 17 km).

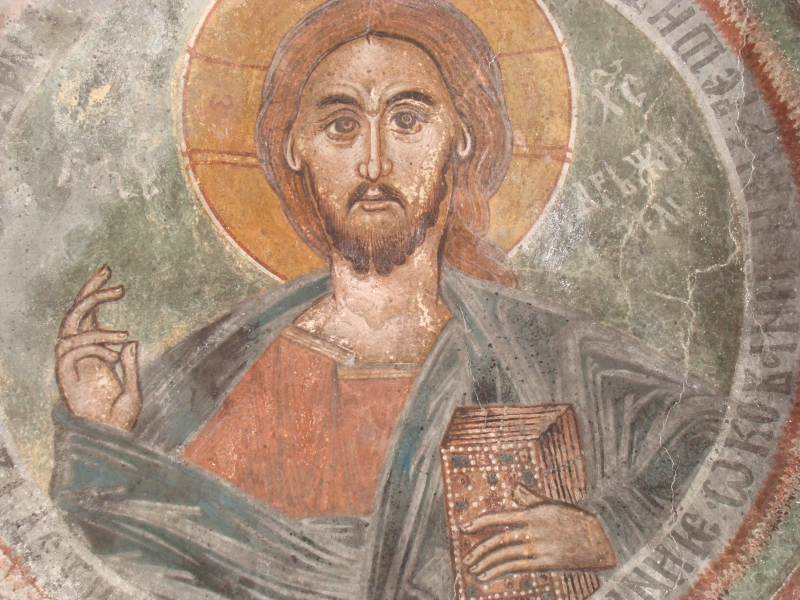

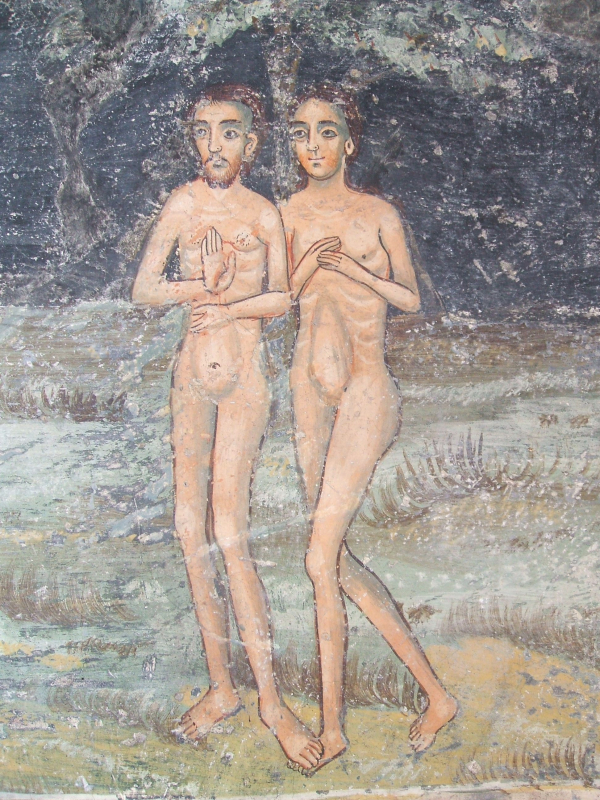

On entering Yarlovo, the road veers to the right, goes past a playground on the right and then heads left into the main square, where there is a Church of St Nedelya, the town hall, a post office and various amenities. Park here. This walk will take you along the course of the Palakaria, up onto the ridge between Yarlovo and Chuypetlovo to the peak Golemiya Rid (with wonderful views north to Cherni Vrah and south to Rila) and back around to Yarlovo. So you leave the main square in the north-west corner and return via the south-west corner.

Take the street that leaves the square in the north-west corner (to the west of the church). It is signposted for Smilyo shelter, Chuypetlovo village and Cherni Vrah via Golemiya Rid. The river Palakaria is flowing on your left. You will pass two bridges going over the river on your left, but just keep going on this street. In half an hour, after the tarmac ends and the road turns into a dirt track, it crosses the river, where there is a pretty waterfall. On the other side of the river, the track begins to climb and turns right (left will take you back into Yarlovo). In fifteen minutes, you will cross a small tributary of the Palakaria, and immediately the path divides. Right will take you along the course of the river. You want to go left, up the mountain. Now stay on this path (with the black and yellow posts), ignore the turning on the left that appears immediately. The path divides and then comes back together (it doesn’t matter which branch you take) and in little more than ten minutes it emerges into the open.

Another ten minutes, and you will reach post number 158. A path on the left will take you to Smilyo, Chuypetlovo and Bosnek. Go right here, in the direction of Cherni Vrah. You will pass a farm outbuilding on the left and then a small house. Follow this path for twenty minutes. It then divides. The right branch will continue taking you in the direction of Cherni Vrah, the summit, but we are going to go left here, in the direction of Golemiya Rid peak. 200 metres after this left turning, there is a path through the grass on the left. In ten minutes (500 metres), this path will take you to the peak, which is a good place to stop for rest and refreshment. Halfway there, a path diverges on the left – ignore it, and in no time at all you will be at the peak. North of here is Cherni Vrah. To the right of Cherni Vrah is Yarlovski Kupen, the main peak at the head of the Palakaria valley. North-west is the village of Chuypetlovo, which featured in our previous walk. And south-east is Yarlovo and the mysterious peaks of Rila, the highest point in the Balkans, in the distance.

Once you have had time to enjoy the views, return to the path you were on and continue left. In about twenty minutes, you will reach a clear crossroads with a picnic area on the right. The left branch will take you to post number 158 and the farm outbuilding, from where you can return directly to Yarlovo. The right branch takes you down to the road just before Chuypetlovo. Keep straight, in the direction of Klisura village. After a hundred metres, ignore the turnings on the right and stay on the path you are on. In half an hour, it divides (the right branch goes to a “cheshma” or fountain). Keep left here, and in five minutes you will come to a T-junction. The right branch goes to Klisura. You want to head left, back to Yarlovo three kilometres away. The road is now tarmacked.

When you reach the first houses in Yarlovo, there is a dirt track on the right, which soon becomes tarmacked as it enters the village, running alongside the river Palakaria on your left. After ten minutes (800 metres), cross the bridge on your left and in five minutes you will enter the main square from the south-west.

Please note: it is easily possible to shorten this walk in two ways. The first is to take the left turning at post 158 and to walk in the direction of Chuypetlovo, not Cherni Vrah. This will omit the peak Golemiya Rid. When you get to the crossroads, take the left turning for Klisura village and continue as per the description. Alternatively, having climbed the peak, when you reach the crossroads, instead of continuing in the direction of Klisura village, turn left here for Yarlovo. You will return to post 158, where you can turn right and descend into the village the way you climbed up. Both options will reduce the walk by several kilometres.

A map of the walk in relation to the whole mountain, with the outskirts of Sofia visible in the top right-hand corner: