In the documentary film “Finding Harmony: A King’s Vision” being released on Friday, His Majesty King Charles III makes the point that we should be living as a part of nature, and not apart from it. We should not see nature as something out there to be exploited, rather we should see ourselves as being interconnected with the rest of nature and reliant on it for our well-being (both physical and emotional). In this short piece, I would like to suggest that language agrees with him.

Let us start by looking at where the idea of separation comes from. You can only see something, such as the environment, as being there to be exploited if you view it as being separate from yourself. If it is a part of you, you won’t want to exploit it. Separation comes from our ability to count. To count something, you must draw a line around it, otherwise you cannot count it. This is why we have uncountable and countable nouns. Uncountable nouns tend to be concepts, things that are too large or woolly for us to comprehend (to draw a line around). Countable nouns are things we can contain – in our imagination, or literally, in a bag or a bottle – and they are preceded by the indefinite article a or an. So, we might have rice and a bag of rice, or milk and a bottle of milk. The first is something that flows constantly, it seems to have no beginning or end; the second is contained (and note that it is the container, the bag or the bottle, that causes so many problems to our environment, it is our drawing a line around something in order to trade in it – in order to count it – that causes pollution).

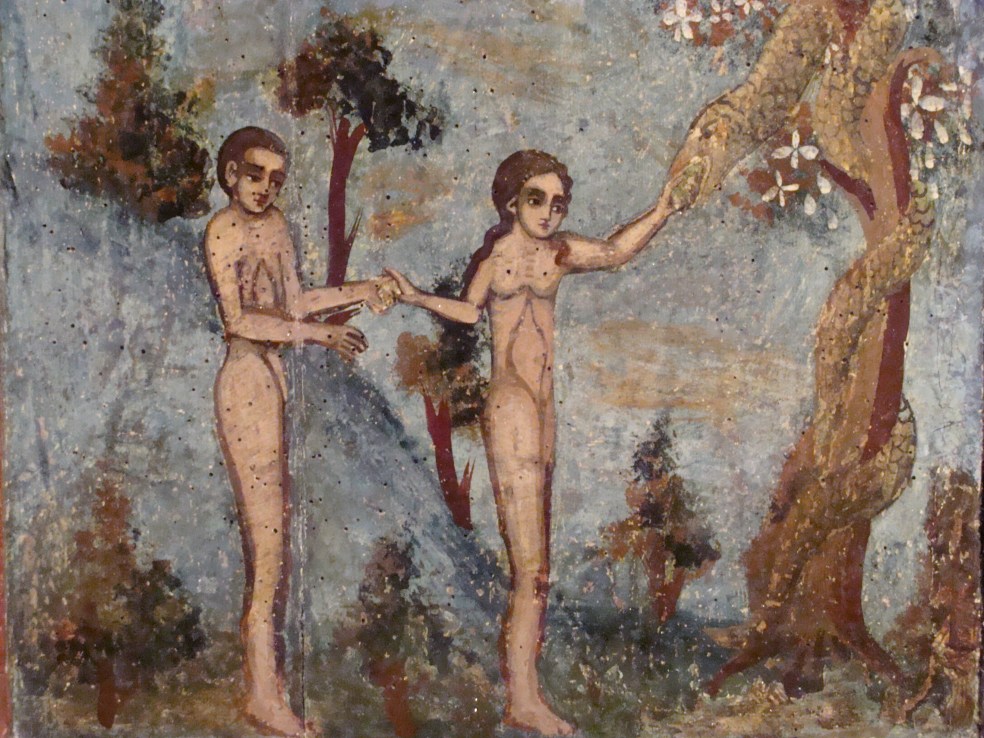

God is uncountable. He is without limits. He is too large for us to comprehend. In the Creation, recounted in the opening two chapters of the Book of Genesis, what he did in effect was make himself countable. He made individual creatures and a planet for us to live on. Creation is the act of making the uncountable countable.

The name of God in Exodus 3:14 (the name he reveals to Moses at the burning bush) is AM. If we apply the phonetic pair m-n to AM, we get an. Language here – with a simple change brought about by applying a phonetic pair – is showing us how God made himself countable, because the indefinite article precedes countable nouns. Read these two words, AM and an, differently, and you get a man.

Man’s purpose was not to create. That is God’s job. We cannot create out of nothing, we can only give meaning to what already exists. We are not authors, we are translators, since nothing begins or ends with us, things pass through us (and we pass through them).

Read the word man in reverse and add a final e (very common in English), and you get name. This was man’s purpose: to name the creatures (Genesis 2:19). By naming them, he gave them meaning, he said amen to God’s will. All three words – name, mean, amen – have the same letters.

But we can go a different way. If I take a step in the alphabet, from m to l, and add the letter d, from man I get land. This is where man lives (hence the importance of nature). If I apply the phonetic pair d-t and add the letter p, from land I get plant, because this is what man must do in order to eat something, he is reliant on nature in order to survive. And if I add the letter e, I get planet. This is what the planet is for – for man to plant crops. God has given him a home.

But whereas God made us countable in order that we might have free will and make our own choices, we have taken this countability to mean that we can do with other people and things whatever we like. We have abused the relationship. We have put the ego first (not God). This is the relationship that we need to repair.

Exploitation is a result of countability (you cannot exploit something unless it is separate). So, we need to repair this breach, or at least to view it in a different light (as something to be respected, for example).

King Charles III explains how nature works in cycles; language also demonstrates this. We start with a seed. The first thing a seed does is sleep. I have rotated the letter d and added the straight line represented by the letter l. This is what we do in our lives when we are oblivious to our surroundings. That straight line represents the ego (it doesn’t matter whether it is written with a capital I or a lowercase l). Once it is in the ground, the seed dies (front vowels e-i). But it dies in order to bear fruit, to become something bigger (a tree). Nature is showing us the path to be taken by the ego – it must die to itself, to its selfish desires and fears, in order to grow in stature.

The seed puts out first a root and then a shoot. These words are connected (mid-vowels e-o, phonetic pair d-t, alphabetical pair r-s, addition of h). The root divides into two, while the shoot – which, as it appears above ground, looks remarkably like a tooth – becomes a tree and divides into three. The tree puts out branches (it doesn’t remain as a straight line), it grows leaves (to harness the power of the sun) and flowers (to attract insects), and the flowers give way to fruit. Fruit is just root with an f on it, and so we return to the beginning… Language is showing how nature is cyclical (in fact, the word return is in nature).

I think this is what His Majesty, with his attention to the importance of the environment, is encouraging us to do – to return to nature. Not to see ourselves as being cut off from it, but as a part of it, reliant on it not only for our physical needs, but also for our peace of soul. It’s like a neighbour – if you are at odds with your neighbour, how can you live peacefully?

The environment attends to our physical needs (without it, we will not be able to eat and we will die). It is beautiful to look at and it gives us peace. But this is not its ultimate purpose. I believe that nature, the environment, is an example out there for what should be happening in us. We also need to bear fruit, not just nature. We also need to die to our selfish impulses for the greater good, just as a seed does when it sprouts in the ground.

In the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 13, there are two parables that teach us about this. One is the Parable of the Sower. This also is a metaphor out there for something that should be happening in here. A sower goes out to sow. Depending on the ground’s receptivity, the seed takes root or it doesn’t. This is really about our ability to hear the word of the kingdom and, having heard it, to bear fruit in God’s name.

If the earth is a metaphor out there for what should be happening in here, then what is our earth? The answer is very simple. Take the last letter of earth and tack it on the front. You have heart. The heart is the earth where the seed of God’s word has to take root and bear fruit. That is the message – of Jesus in the Gospels, but also of nature.

We have to be able to see and hear in order to bear fruit in God’s name – Jesus places great emphasis on our ability to see and hear – and for this we need to learn humility. The humility to admit that our sight has been imperfect, which ironically is what then enables us to see.

I mentioned the phonetic pair d-t earlier. Add this pair to see and hear. What two words do you get? Seed and heart. Language is telling us that when we see and hear the message of the kingdom, a seed is planted in the earth of our heart and we are enabled, through the intervention of the Holy Spirit, to bear fruit. Nature is a lesson out there for what should be happening in here. When we become spiritually healthy, then we will treat the environment as it deserves.

And just in case we were in any doubt, Jesus provides another example: the Parable of the Tares (again, in Matthew 13). Someone sows good seed – the wheat, the children of the kingdom – but an enemy comes in the night and sows weeds – evildoers. The slaves of the householder ask whether they should remove the weeds, but the householder says to wait until the harvest (the end of time), in case they uproot the wheat as well.

Weed and wheat are connected (phonetic pair d-t, addition of h). They look alike, just as people in society look alike and we cannot always be sure of their intentions. But there is one fundamental difference. There is something that wheat has that a weed doesn’t, and that is ears. Wheat is able to listen.

Nature is an example out there for what should be happening inside us. The seed is the word of the kingdom – to love the Lord your God, to love your neighbour – and that seed should be sown in our heart, just as a physical seed is sown in a field. When this happens, we learn how misguided we have been, we learn humility, and we redirect our priorities towards the kingdom (this is the meaning of repentance, metanoia in Greek). We also bear fruit, just as a tree does. And once we can see, the rest of creation rejoices. It recognizes us for the first time. We establish a relationship that is one of love and care, which is King Charles’s message in his film “Finding Harmony: A King’s Vision”.

Jonathan Dunne