Further east towards Samokov, but also on the north side of Rila Mountain, is Rilska Skakavitsa – ‘Rila Waterfall’ – the highest waterfall in Rila at 70 metres. It is situated south of the spa town of Sapareva Banya, very near the famous Seven Rila Lakes, which are further south (the closest lake to the waterfall is the fifth lake, the ‘Kidney’). I have visited this waterfall at different times of year – in thick snow during March, when there were very few people about except snowboarders, and surrounded by lush vegetation in July. They make for very different experiences!

To visit this waterfall, you must take the A3 motorway that connects Sofia and the border with Greece at Kulata. You are going to go as far as Dupnitsa, a distance of 60 kilometres. To reach Dupnitsa, you must leave the motorway six kilometres before the town and follow the old national road into the town itself, past a series of car dealers. 600 metres after entering Dupnitsa, just before the OMV petrol station, turn right (it is signposted for Sapareva Banya). At the bottom, go left under the national road and over a railway. After 300 metres, turn left at the traffic lights (signposted for Samokov and Sapareva Banya), and follow this road along the north side of Rila Mountain.

After 11 kilometres, there is a turning for Sapareva Banya on the right. You will need to go through the town and continue to the resort of Panichishte. After entering the town, go right at the roundabout and follow this road, which then veers left. At the stop sign, take the road diagonally opposite and continue uphill. At another stop sign, turn left. You are now on the road to Panichishte, which is ten kilometres from Sapareva Banya. On entering Panichishte, ignore the hotel signposts pointing left. Continue on the same road, and you will pass a tourist information centre on the left. Keep going for another 3.8 kilometres, until you reach a turning on the right that goes uphill to a place called Zeleni Preslap. You need to park the car here and continue on foot.

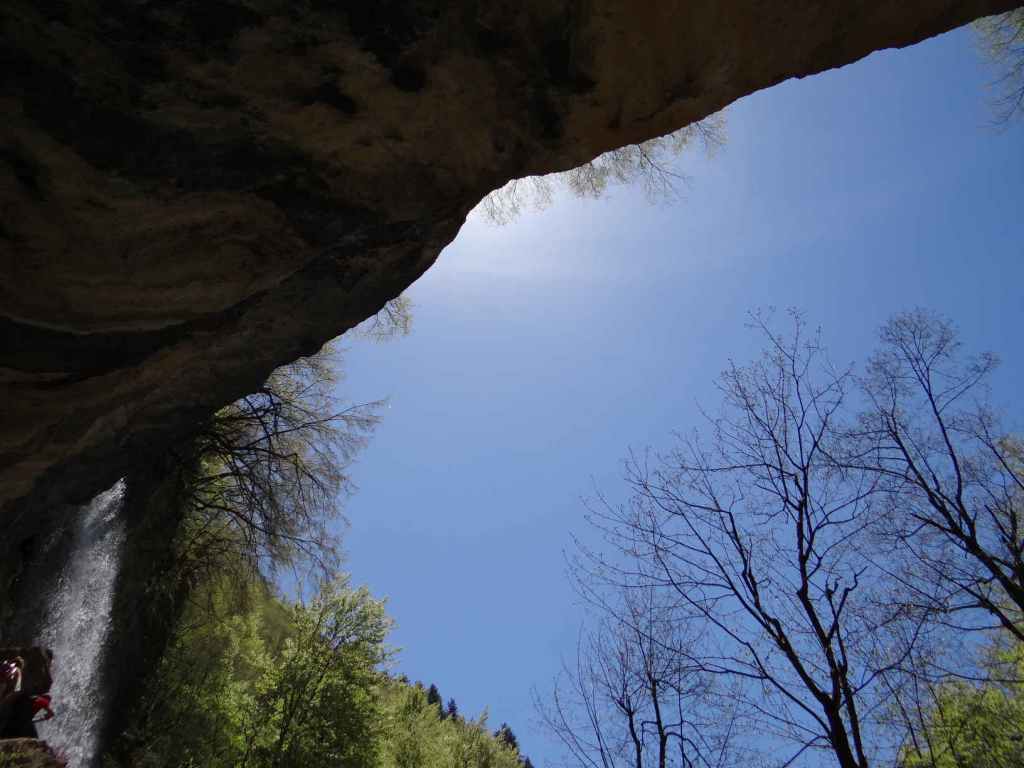

The walk is 11.5 kilometres, there and back, and in the snow in March it took us five hours. Factoring in the driving, that meant a day trip from Sofia of nine hours. The elevation gain is 475 metres, and there is quite a steep climb between Zeleni Preslap and Skakavitsa Hut, as you go through the forest, but the waterfall is eerily magical and well worth the effort. Just the fact you are a short distance from the Seven Rila Lakes is enthralling.

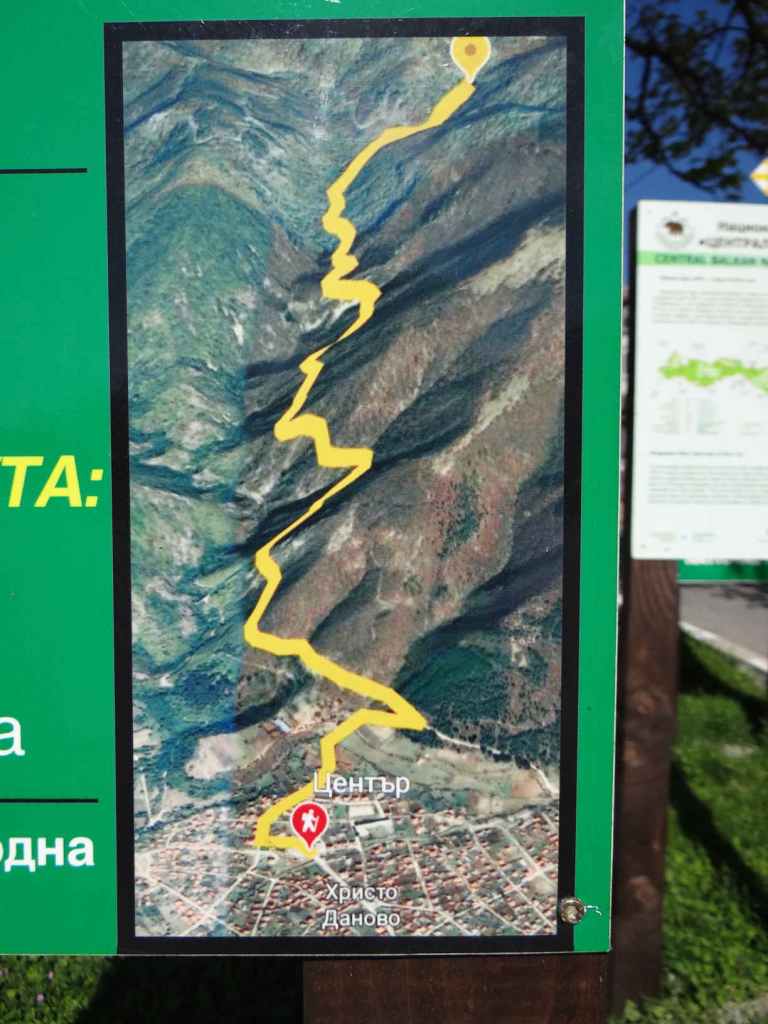

After 850 metres, you reach the rest house at Zeleni Preslap. Keep the rest house on your right and take the path that heads due south, to the left of some information boards. Continue on this path, with trees on either side, for 1.5 kilometres, then take the path on the right, signposted for Skakavitsa Hut and Kabul Peak. This path climbs gently at first, then more steeply. After two kilometres, a path on the right diverges to Kabul Peak. Keep left, and in 150 metres you will reach Skakavitsa Hut. The hut is open for refreshments in the summer, but not in March, when the ground is covered in thick snow and the only creatures we came across were a crestfallen guard dog and a large, standing wooden bear. The path to the waterfall is another 1.5 kilometres further south and takes about 40 minutes (in the snow). There are wonderful views of the waterfall and surrounding cliff faces as you approach.

The road from Panichishte continues to Pionerska Hut, where there is a controversial lift that makes it much easier for daytrippers to access the Lakes. Purists, and I’m inclined to agree with them, would say you should do the walk on foot, but no doubt the lift serves a purpose. The name of the mountain, Rila, comes from a Thracian word meaning ‘watery’. You will notice this when you are on the mountain – you often seem to be stepping in water. The Galician word for ‘kidney’ is ril – it seems to me that Rila, the main water divide separating the Black Sea and the Aegean Sea drainage systems, functions as Bulgaria’s kidney, and indeed the waterfall resembles a kidney, as does the glacial lake nearest to it.